I’m not the first to try to aggregate fictional or fanciful maps (see Andrew DeGraff’s Literary Atlas, Umberto Eco’s Book of Legendary Lands and this article on maps in children’s books, for example), but I am eager to hear back from literary explorers that I can trust in a personal or particular way, if anyone wants to send recommendations or pictures of middle-school class projects to ben@1001goodnights.com.

I don’t remember who gave me my favorite childhood birthday present, Rand McNally’s Historical Atlas and Guide. Even more embarrassingly, I do remember steering casual conversations toward Map #19: (“Greek and Phoenician Settlement in the Mediterranean. CA 750-550 BC”). I felt very comfortable talking about Map #19, in the same unfortunate way I felt comfortable grilling volunteer museum guides in front of dinosaur exhibits. That is the problem with maps; they can encourage a false sense of superiority about places you have never even been.

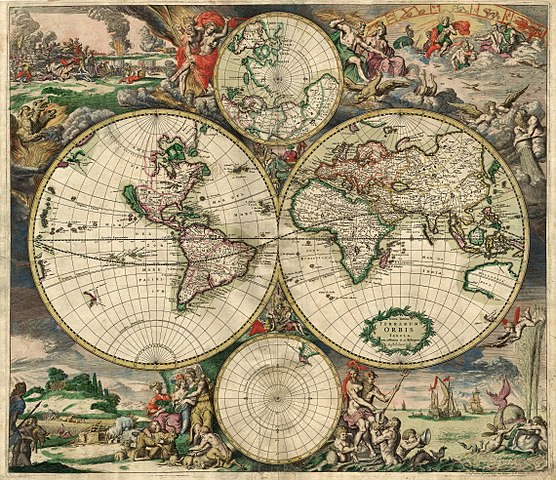

On the other hand, people find their way to a false sense of superiority about places they have never been just fine without maps. In fact, maps are ostensibly intended to provide the curiosity and confidence to actually go to those places. Or are they? What about Map #80: (“Renaissance Italy after the Peace of Lodi 1454”), which will never help me find a grocery store, much less enable a trip to the fifteenth century? What use are maps of places to which we can never go? For that matter, what is the purpose of the maps strewn across works of fiction? Are they just visual aids for feeble readers who can’t follow a plot without a diagram?

To be clear, I’m grateful for visual aids. I’m the kind of feeble reader who survived Shakespeare by ceaselessly flipping back to the cast of characters to keep the assorted noble cousins straight. I am all in favor of helpful reference resources. But maps of impossible places often transcend that role, serving less as an instrument and more of an invitation. Rather than just helping track the characters as they plod along their narrow narrative arc, the best maps of fiction also give the reader a chance to explore the wider world of the story, even those places the protagonist will never go. The map on the front flap is a pass to explore the possibilities of the imaginary place all at once. When the map is repeated on the back flap, as it frequently is, it is a chance to eye the unused topography as real estate for other stories, even if those stories are your own.

Tolkien, of course, was a master of this kind of cartography, though sometimes I got the sense from his appendices and his extensively-published world-building notes that he had a plan for every stray corner of his maps and might resent non-canonical trespassing. I brooded over the maps of Middle-Earth anyway, until I had them in my bones. And really good fictional maps, like really good stories, are only enlarged by experience in the real world. The first time I looked down on a West Virginia valley shrouded in fog, I felt I understood the Misty Mountains a little better. I realize that is almost as insufferable as saying I traveled Sicily to enhance my experience with Map #80. Maybe it is better to say that maps hint at the possibilities of a wide and wonderful world and it is a special kind of pleasure to have them proved right. Or maybe it is better to say that maps work on a principle of comparison; they are improved when they are taken into the field and compared with other maps. With the exception of a secretive subcategory of treasure maps, maps are a communal endeavor.

So I am curious what maps of impossible places my fellow-readers carry with them. And what makes one work better than another beyond a well-shaded forest?

Leave a Reply