Children’s literature has evolved to some pretty spectacular heights.

When you consider the visual grandeur of recent children’s books like Journey or the pitch-perfect prose of Library Lion, it’s hard not to look back on the Golden Books or Pat the Bunny as primitive, if necessary, evolutionary precursors to today’s big guns.

Still, there’s a case to made that we may have lost something along our evolutionary way. Though contemporary children’s books have become more sophisticated in their literary nuance and artistic grandeur, this may have come (perhaps unconsciously) at the cost of something psychological profound and essential.

That’s the argument, anyway, psychologist Bruno Bettelheim puts forth in his intriguingly-titled book The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales.

The Psychology of Fairy Tales

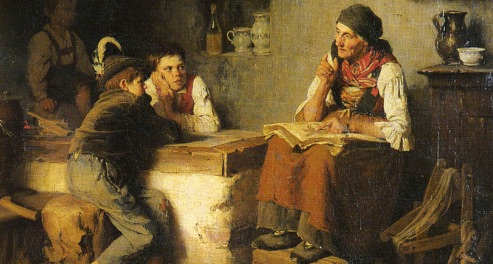

Bettelheim claims fairy tales contain specific properties that uniquely help children to process the normal but challenging tasks of psychological and emotional development:

these tales, in a much deeper sense than any other reading material, start where the child really is in his psychological and emotional being. They speak about his severe inner pressures in a way that the child unconsciously understands, and—without belittling the most serious inner struggles which growing up entails—offers examples of both temporary and permanent solutions to pressing difficulties.

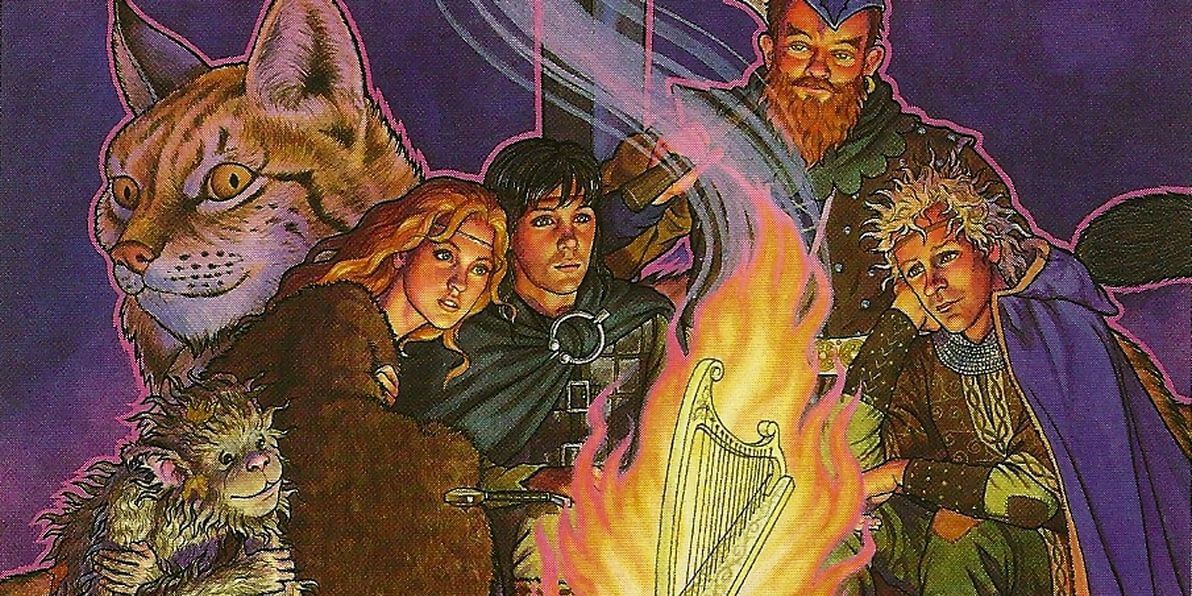

More specifically, it’s the grit and terror of traditional fairy tales that helps children come to terms with their own inner struggles—many of which are similarly dark, painful, and even grotesque.

In “Little Red Riding Hood” the kindly grandmother undergoes a sudden replacement by the rapacious wolf which threatens to destroy the child. How silly a transformation when viewed objectively, and how frightening—we might think the transformation unnecessarily scary, contrary to all possible reality. But when viewed in terms of a child’s way of experiencing, is it really any more scary than the sudden transformation of his own kindly grandma into a figure who threatens his very sense of self when she humiliates him for a pants-wetting episode?

The fairy tale’s tendency to split things into dichotomous opposites—so psychologically simplistic to our modern adult sensibilities—is a crucial developmental aid for the child who needs to learn how to reconcile, for example, good and bad within a single person if they’re to achieve psychological maturity:

Unable to see any congruence between the different manifestations, the child truly experiences Grandma as two separate entities—the loving and the threatening. She is indeed Grandma and the wolf. By dividing her up, so to speak, the child can preserve his image of the good grandmother. If she changes into the wolf—well, that’s certainly scary, but he need not compromise his vision of grandma’s benevolence.

As adults, parents, and even—I suspect—children’s book authors, our natural tendency is to shield and protect our children from pain, terror, and other frightening experiences, especially the “unrealistic” variety.

the prevalent parental belief is that a child must be diverted from what troubles him most: his formless, nameless anxieties, and his chaotic, angry, even violent fantasies. Many parents believe that only conscious reality or pleasant and wish-fulfilling images should be printed to the child… But such one-sided fare nourishes the mind only in a one-sided way.

But pain, terror, and unrealistically frightening things are fundamental to the experience of growing up. And it’s only when these fears are validated that we are prepared to face up to them and overcome them.

This is exactly the message that fairy tales get across to the child in manifold form: that a struggle against severe difficulties in life is unavoidable, is an intrinsic part of human existence—but that if one does not shy away, but steadfastly meets unexpected and often unjust hardships, one masters all obstacles and at the end emerges victorious.

For Bettlheim, this is the great unintended travesty of modern children’s literature: by making our children’s books too clean and “safe,” we remove their most important psychological function of validating our children’s inner experience and helping them to confront it in a developmentally appropriate way:

The worst features of these (modern) children’s books is that they cheat the child of what he ought to gain from the experience of literature: access to deeper meaning, and that which is meaningful to him at his stage of development. For a story truly to hold the child’s attention, it must entertain and arouse his curiosity. But to enrich his life, it must stimulate his imagination; help him to develop his intellect and to clarify his emotions; be attuned to his anxieties and aspirations; give full recognition to his difficulties, while at the same time suggesting solutions to the problems that perturb him… promoting confidence in himself and his future.

Choosing Our Tales Wisely

As parents, allowing our kids to suffer even the smallest dose of fear or inner pain goes against our every instinct. And it doesn’t take much of an imaginative leap to consider that this built-in predisposition manifests itself in the books we choose to read (or not read) to our children. We play it safe at story time—choosing books that entertain, delight, and encourage, while tacitly avoiding those that terrify or startle.

But as a psychologist who helps adults navigate their own anxieties and fears on a daily basis, I can attest first hand to the subtle dangers inherent in avoiding our fears. The temporary relief of avoidance and distraction only perpetuates the very fears and insecurities we struggle with.

Only by confronting and validating our deepest fears—however unrealistic or irrational—are we’re able to overcome them and move on with our lives, finally free to move toward our aspirations rather than running away from our anxieties.

Whatever stories we choose at bedtime, it’s worth considering what they’re doing for our children’s psychology. Any decent children’s book will likely contribute to a bigger vocabulary and elicit a few laughs before bed. But how many will be aiding our children in their deepest struggles of emotional and psychological development?

Perhaps it’s only the grimmest of tales that’s up to that challenge.

Leave a Reply